STATUS OF PERNAMBUCO

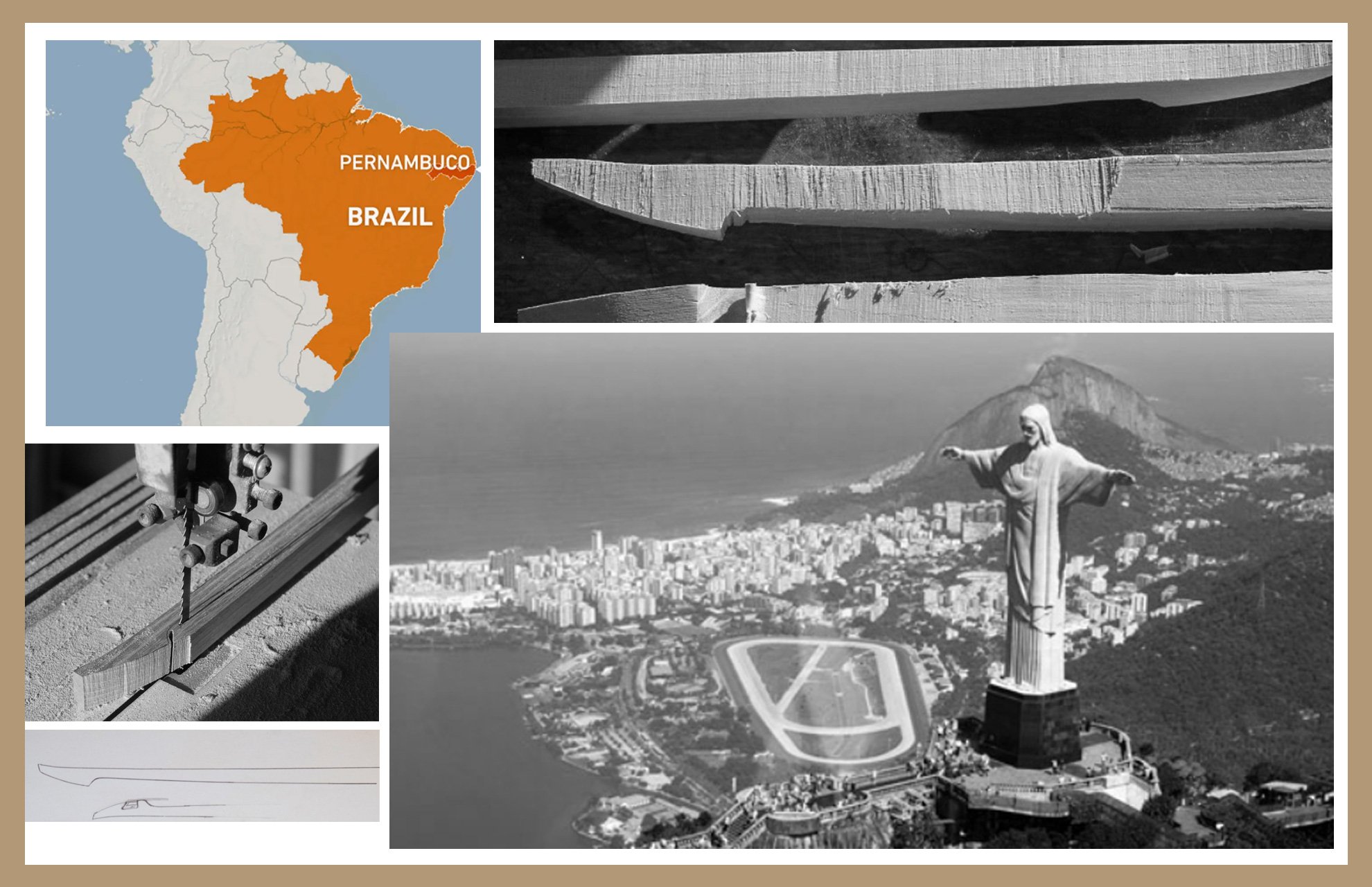

Pernambuco, the common name of Caesalpinia echinate, is a fascinating wood, and one that is seriously threatened by extinction from overuse and rampant deforestation of the region in which it grows. It is a hardy wood, but one that is dependent on the endemic species in the region in which it grows: the coastal region of Brazil. For centuries, Pernambuco has been the king of bowmaking wood: its unique long-fibered cell structure (it is a bean plant after all) coupled with high density makes it truly unique among wood species and particularly well suited for bow making.

Originally, this wood thrived in Brazil and was so common the entire region was named for it. Pernambuco’s red colouration was a critical part of the textile industry of pre-Industrial Revolution Europe and it was heavily exported for this purpose…until such time as synthetic dyes replaced it. Today, little use is there for Pernambuco besides bow making…but this sole usage is extremely lucrative and brings a huge income to the area.

At one time, the forests of the Pernambuco region were the size of New York. Today, it is more the size of Delaware. Huge tracts of forest have disappeared and the Pernambuco wood is no longer so plentiful. But as supplies diminish, the prices for this wood have increased creating a large incentive for foresters, sawyers and bowmaking companies in Brazil to bring the wood to market to service the demand: a demand that has grown exponentially in the last several decades with the increased bow and violin manufacturing that has exploded around the globe.

Pernambuco is an endemic species. This means, in short, that it relies on the biome in which it grows to reproduce and prosper. For this reason, it is a very difficult species to grow outside of the unique conditions of coastal Brazil. It is also not a wood that lends itself well to plantation-style cultivation. It thrives with a certain collection of friendly species one of which it is mutually co-dependent.

As the state flower, Pernambuco is an important part of the Brazillian heritage and the government of Brazil has a long history of trying (and in most cases failing) to preserve it. Harvesting of wild Pernambuco has been illegal in Brazil from as far back as the early 1990s and while the governments of Brazil had varying interests in the enforcement of environmental regulations, laws on the books in Brazil sought to ensure that this important resource would continue to be a part of the eco-landscape for the indefinite future.

But the wood is valuable. Very valuable. Companies in Brazil sprang up during the 1990s and 2000s and Pernambuco continued to be forested and shipped either as raw wood or as finished bows into the world market. Much of this trade was illegal and many arrests were made, and penalties assessed. But the black market trade continued. Because the laws of Brazil have no bearing on the importation restrictions, the challenge, if it was a challenge, was to get the wood out of the country. Once exported, importation into Europe, North America or Asia was easy and unrestricted.

International law can protect rare, threatened or endangered species. Such protection is managed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, for short), a global agreement among world governments passed in 1975 to protect our biodiversity. CITES is the reason, for example, that Ivory, or Ivory products, is not exportable, nor whalebone, tortoise or other endangered species. CITES is the international legal arm of the Endangered Species Act and it gives weight to national efforts, like those in Brazil, to restrict trade and preserve resources from overuse and overconsumption.

The judicial arm of CITES meets every three years and creates the “rulebook” for endangered species, placing them into one of three CITES classes. A CITES Appendix 1 listing, is the most extreme: these are reserved for species facing imminent risk of extermination and receive the highest level of protection. In 2007, at the request of the Brazilian equivalent of the Dept of the Interior (IBAMA), CITES put Pernambuco on Appendix II, a strong statement of concern for the species. With this distinction, Pernambuco wood became internationally protected with raw wood illegal for harvesting, import or export. Finished products, like bows, were fine for international trade, but the raw wood was not.

Many European bowmaking companies began a careful inventory of their wood. Pernambuco “shopping trips” to Brazil were no longer allowed, so the (large) stockpile of wood in Europe became the legal resource available to bowmakers. As long as this wood was listed as predating the CITES II declaration, the wood was fine for use in bowmaking, and their customers could buy and sell their bows freely.

The CITES II listing, however, was only as effective as its enforcement. As stockpiled Pernambuco in Brazil (that is, wood certified by IBAMA as legally harvested prior to the legal restrictions) declined, and bow prices rose, the incentive to illegally harvest the wood, make bows illegally from this illegal wood, and/or smuggle the wood into other countries, was ever increasing. The Brazillian government watched as the forests continued to be forests; the Pernambuco resources declined.

This brings us to 2022 and the most recent convocation of the CITES meeting. Following years of lacklustre adherence to conservation laws, IBAMA brought to CITES a request to elevate Pernambuco’s protection to Appendix I. Had this passed, all international trade and transport of Pernambuco bows would be restricted to bows manufactured prior to the new rules going into effect from wood that was legally harvested. Bows would require a CITES certificate of legality to cross international borders.

IBAMA’s Proposal was rejected by CITES, but with caveats that should be very concerning to the bowmaker’s trade. While unwilling to elevate Pernambuco to Appendix 1, they did put Pernambuco under heightened restrictions. All Pernambuco wood, including finished bows, would now require a CITES permit to be exported from the originating source of the wood, ie Brazil. European countries, for example, can export their bows as no Pernambuco grows naturally in Europe, but Brazil cannot do so without subjection to the permit process.

And, notably, CITES committed to revisiting the issue at their next meeting in 2025.

In the meantime, they cautioned, the bowmaking and Pernambuco wood trade needs to step up their efforts to self-regulate. They need to put systems in place to legally certify the legitimacy of wood and bows and need to, in general, support the efforts to protect an endangered species.

For bow dealers, makers and players, the lessons are clear. Already, bows from Brazil have become very hard to find, and Vermont Violins joins the movement among dealerships to limit our Pernambuco sales to include makers that are certifying their woods and abjuring the use of illegal, blackmarket, materials. If we all do this and work in cooperation with regulatory agencies like the Fish and Wildlife Department of the US State Department, we can ensure the healthy use of a unique wood for generations to come. Failure to do so will ensure that we will be unprepared for legal changes in 2025.

Players: Know your Bow. Understand the materials used to craft your bow and your instrument and consider the sourcing of these materials as part of your understanding of your instrument. If you are shopping for a new instrument or bow, include the materials used as part of your consideration, along with tone, workmanship, attribution, provenance and your other considerations. Doing our part to be responsible stewards will ensure that our music will truly make the world a better place.